How has defence spending increased globally?

Total military spending by nation states reached $2.72 trillion in 2024, a rise of 9.4% in real terms on the year before, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. That’s the tenth consecutive year of increases, and the steepest year-on-year rise since at least 1988 – and takes spending on defence to about 2.5% of global GDP. The world’s biggest spenders are the US, China, Russia, Germany and India; together, these five account for about 60% of the total. Last year, spending increased in every region of the world – with especially strong growth in Europe and the Middle East – as geopolitical tensions grew. Average military spending as a proportion of overall government expenditure rose to 7.1%, while world military spending per person was the highest since 1990, at $334.

Which countries saw big jumps in defence spending?

Israel’s spending surged 65% to $46.5 billion – the steepest annual rise since the Six-Day War of 1967 – taking its total to 8.8% of GDP, the second highest in the world (after Ukraine’s 34%). Lebanon’s spending rose by 58% to $635 million; Iran’s fell 10% in real terms. The Middle East’s biggest spender is Saudi Arabia, with an estimated $80.3 billion. But it saw a modest rise of 1.5% and real spending is 20% lower than a decade ago, when the country’s oil revenues peaked. The biggest jump in spending in Asia was in Myanmar, where it rose 66% to an estimated $5 billion. Japan’s outlay is up 21% to $55.3 billion in 2024, the largest annual rise since 1952. Mexico’s spending rose by 39% to $16.7 billion, as part of the government’s militarised response to organised crime. In Europe, Sweden increased its spending by 34% to $12 billion (2% of GDP) in its first year of Nato membership – a direct response to the increased threat from Russia.

What about the rest of Nato?

Germany’s expenditure rose by 28% to reach $88.5 billion, making it the biggest spender in Europe (not counting Russia, where spending grew 38% to an estimated $149 billion – twice the level of 2015 and 7.1% of GDP). Poland’s spending grew by 31% to $38.0 billion in 2024, or 4.2% of GDP. Total spending by Nato members totalled $1,506 billion ($1.5 trillion), or 55% of the global spend. Easily the world’s biggest spender remains the US, where the total rose 5.7% to $997 billion – that’s 66% of the Nato total, and 37% of the world’s. China, the second-biggest spender, upped spending by 7% to a $314 billion, marking three decades of consecutive growth.

Subscribe to MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Get 6 issues free

Sign up to Money Morning

Don’t miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don’t miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

What about defence spending in the UK?

It raised defence spending by 2.8% to reach $81.8 billion, making it the sixth biggest spender worldwide (France, with $64.7 billion, is ninth). The UK currently spends 2.3% of GDP on defence, but last month – under intense pressure from the US – joined the rest of Nato (except Spain) in promising to raise spending to 3.5% of GDP by 2035, and 5% once further security-related spending is taken into account. If they achieve that target, Nato members will be spending $800 billion more every year, in real terms, than they did before Russia invaded Ukraine.

Will defence spending drive economic growth?

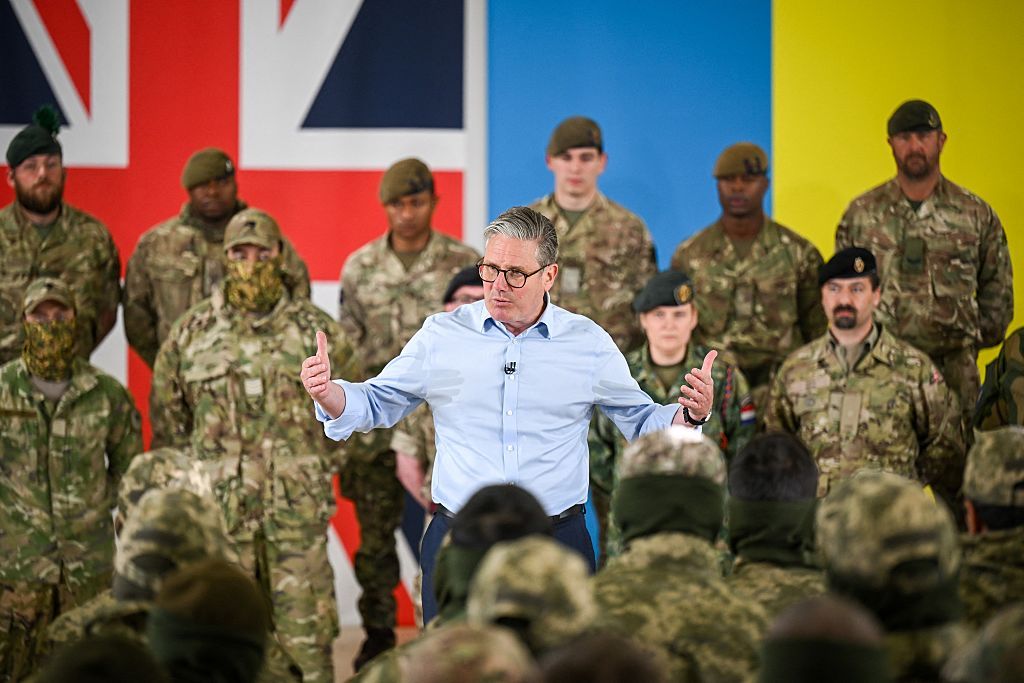

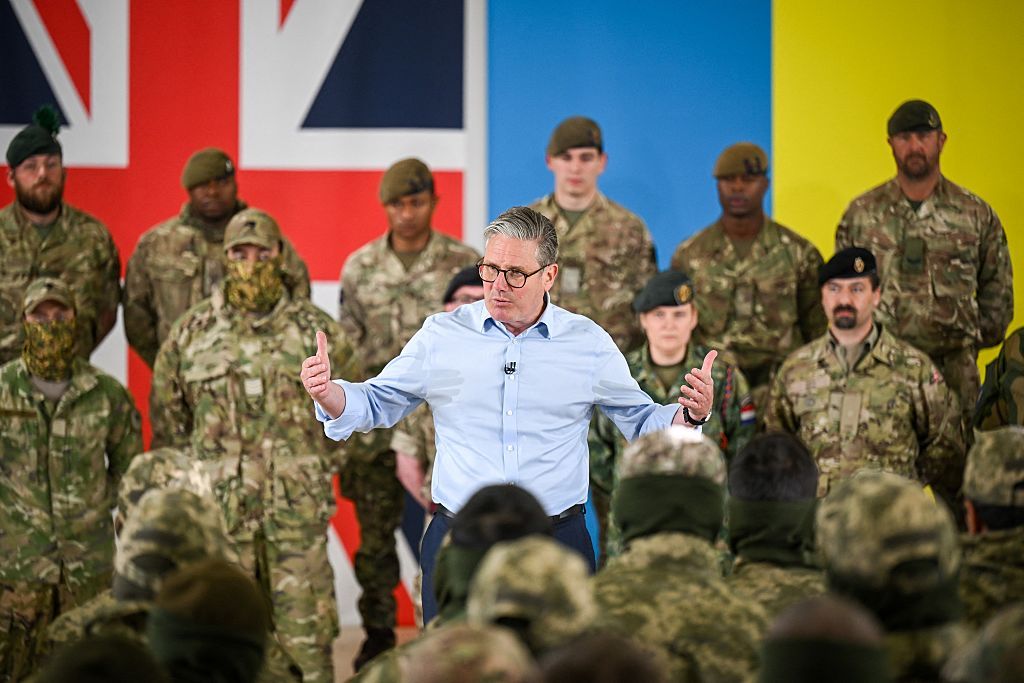

That’s what politicians are telling voters. Keir Starmer says defence will offer “the next generation of good, secure, well-paid jobs”. The European Commission says it will bring “benefits for all countries”. In reality, such hopes are likely to prove forlorn, says The Economist. Rather, the “most obvious economic consequence of bigger defence budgets will be to strain public finances”, meaning higher deficits and probably higher interest rates – none of which will aid growth.

Historically, military spending is “not a major growth booster”, agrees Pierre Briançon on Breakingviews. A recent paper by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy found the “fiscal multiplier” is often lower than one – meaning that a rise of 1% of GDP in military spending triggers an overall rise in GDP of less than 1% in the short term. Similar analysis by Goldman Sachs estimates that the multiplier in Europe is even lower, at 0.5, meaning that for every extra €100 spent on defence, the region’s GDP rises by just €50.

So defence spending is nothing to get excited about?

Any long-term economic effects will depend on where the extra money comes from and how it is spent. According to Ethan Ilzetzki, professor at the London School of Economics and the author of the Kiel Institute report, any growth boost will be greater if governments choose to fund it through borrowing instead of higher taxes, which would have a negative impact on growth. This will be much easier for low-debt Germany than for higher-debt Britain and France. Moreover, simply setting targets risks wasteful spending on low-value projects. For the economic impact to be significant, it is crucial to focus the spending on research and development, given that “publicly funded innovation often has the effect of spurring private innovation”, says The Economist. Currently, for the EU, expenditure on research and development is a paltry 4.5% of defence spending, compared with 16% in the US.

What else will help?

Greater pan-European co-operation and integration – importantly, including the UK – and a shift away from buying American. Europe’s most pressing need is to create its own “strategic enablers” independently from the US, says Hugo Dixon, also on Breakingviews. That’s military-speak for projects such as satellite-based intelligence, air-defence shields, and a joint command and control system. Such things are expensive and technologically complex, and it makes sense to create them collectively. To get the biggest bang for their buck – militarily and economically – Europe needs to favour its domestic industry. Imports currently account for more than 80% of Europe’s defence procurement, of which three-quarters comes from the US. “To manufacture more weapons at home, national capitals would have to agree common strategic needs, pool resources and keep restructuring the defence sector.”

This article was first published in MoneyWeek’s magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.